Fortunately, the executioner is played by Richard Linklater, one of those who breaks the comfort of life to fuel romantic stories about the condition of modern man. In “Hit Man,” a stoic individual’s daily life is turned upside down by an unexpected promotion. Previously a police technician behind a desk, Gary now moves into the field, working under the false cover of a paid assassin. An idea straight out of “Minority Report” – our hero plays the role of a hitman, waiting to be delivered the envelope containing the money, and eventually putting the leads in jail. And against all expectations, it is devastatingly effective at it.

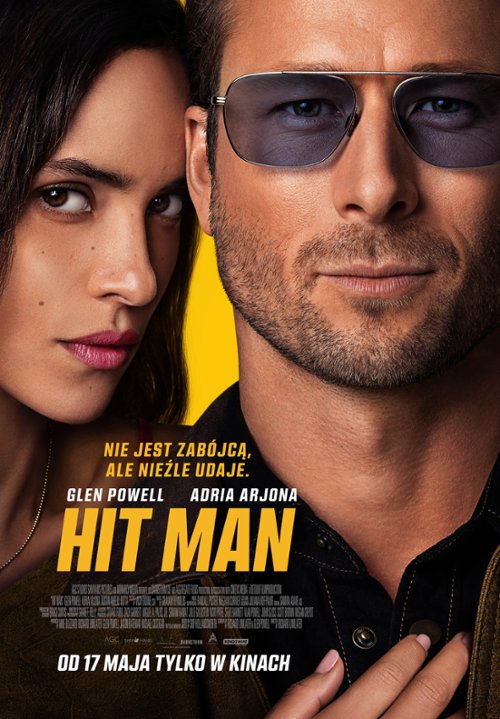

Glen Powell Linklater helped write the screenplay. However, this seemingly insignificant nuance is of great importance to the final form of “Hit Man.” The film’s plot, often at the expense of internal coherence, becomes a theatrical stage for the actor’s transformations, highlighting Powell’s still widely unrecognized potential. The party of endless transformations resembles the tactics of “Holy Motors” in the “Hollywood Mainstream” version – each subsequent order requires a new identity, fully adapted to the needs and personality of the customer. Gary then picks on the author in a parade of mock accents, costumes, and makeup. Sometimes he’ll be a confident lover, sometimes a weirdo, sometimes a vulgar redneck from the South. Even if there’s no plot justification for so many of Powell’s transformations throughout the film, the actor who simpers for the camera is pleasant enough to look at to throw any whiny claims about physique over the left shoulder.

The other thing is that “Hit Man” offers much more than just an eye-catching show. After all, the basis of a crime comedy scenario is conflict, and this shows with the attractive agent Madison (Adria Arjona). Helpless in her relationship with her toxic husband and fearful that she is being set up to kill him, she softens Gary enough for him to question his professionalism for the first time and let her go. From that point on, the hero’s life branches out into three independent characters: a boring academic who drives a Honda Civic, a police ethics officer, and Ron, a charismatic serial killer who plays him for the sake of his budding romance with Madison. Freud’s description of the id, ego, and superego, which Linklater divided into personal, professional, and social positions.

“Hit Man” will regularly search for parallels that combine wisdom from academic textbooks with the comedy of self-lost. What is not here! Nietzsche’s ‘Dangerous Life’, Guy Debord’s ‘Society of the Spectacle’, the debate on the psychological capacity for personality change and ‘conscious subjectivity’ as a convenient construct or individual choice. And before you attack the pseudo-intellectual critic in the comments, let me reassure you: the film explains everything in an accessible way, and sensitively integrates the lecture scenes into the events of the plot. Linklater needs a scientific context for two reasons: first, to show that between rationally understanding psychological processes and drawing constructive lessons from them, there is, in Mateusz Świecki’s words, “a real space of space.” Second, pinning the hero’s profound loss on something beyond the screenwriter’s imagination. The constant balancing act between Virgin Gary and Chad Ron generates not only problems of a logistical nature, but also confusion of identity – the protagonist, not knowing who he is, also forgets who he should be.

On the one hand, the passive satisfaction of a quiet life with two cats, on the other hand, sexy power, high testosterone, a beautiful woman and a noose of lies around her neck. Tragic dilemma? Then add to that an emotionally unstable and potentially murderous husband (Evan Holtzman) and a work friend (Austin Amelio) who begins digging into his private life using the methods of a police detective. Linklater, in Quinn’s style, condenses the web of contradictory connections and motivations, attempting to generalize the main character’s dilemma; Show that there is always a hidden, easily missed gap between your innate, “real” personality and the role you play. However, it does so without any ambition, with the typical lightness of the chosen genre and with plenty of comedic attraction.

In the end, “Hit Man” turns out to be a surprisingly refreshing “summer”; A simple film as if taken straight from the 90s or 00s, i.e. from the times before the emergence of the cool trend of “romance cinema”. With one eye on the classics of “Mr. and Mrs. Smith” and the other on questioning the moral conclusions of “Double Indemnity,” for example, Linklater reflects not only the trends of contemporary cinema, but also those of his author. Cinema. If you want to gradually enter the mainstream from an independent path, it will probably only be through inconspicuous ornaments.

“Amateur social media maven. Pop cultureaholic. Troublemaker. Internet evangelist. Typical bacon ninja. Communicator. Zombie aficionado.”