December 1981. Some said that martial law “protected Poland from state disintegration,” while the majority unequivocally interpreted this event as “a blow to the spirit of Poland, [gdzie] All hopes vanished in an instant. And it is precisely this “loss of hope” that the concerned Mariana (Catarzyna Figura) wants to prevent on the day of the christening of her youngest grandchild. Mariana only dreams of reconciling the already strife family with her sons and daughters. The girls reach the Tatra hut with great difficulty, and the woman does absolutely everything so that they do not know about the sudden decision of General Jaruzelsky.

There is a lot of controversy about him in this family. Even the identity of the father of little Carol, whose entry into the church community is being prepared, is unknown. Mariana’s children have many of their problems and vulnerabilities stemming from unresolved past traumas; Sometimes unable to find their place in the world, they flee into addiction and bitter loneliness. Among the quarrels between brother and sister, the enmity of the two older brothers, Vojtek (Tomasz Schuchardt) and Tadeusz (Mikai Schurawski), which reflects in a typical way the main axis of the then conflict, the division of the homeland into society, emerges. (Tadeusz-Catholic) and power (Communist Wojtek).

“Chrzciny” has the most tragic or even tragic comedy in it. As befits this model, during the fateful day of the title ceremony, there will be many (somewhat) funny skirmishes and misunderstandings, resulting in a bizarre qui pro quo buildup. However, the filmmakers attempt to move beyond the scheme of pure playing with conventions in favor of a broader, in-depth reflection on Polish society and the family. It’s not a movie that feeds on memory, anthropology, and retro-climate. It’s not just a movie about the past, but the past in the background. Although the adventures of Mariana and her extended family were staged in 1981, they are also very reminiscent of our day. The present, which passes under the sign of – as it is often socially defined – the Polish-Polish War. At that time and today, the ceremonially laid table turns into a battlefield for an ideological battle in which one fights with a sharp word and a fork. Everyone feels like a winner, because everyone defended their sacred right. In this way, martial law continues in the family all the time. Jakub Skoczeń, thanks to two lines of history – the individual and the national – talks about overcoming the struggle of one family through a great historical clash. In the end, peace prevails and a special kind of harmony emerging from violence and hostility.

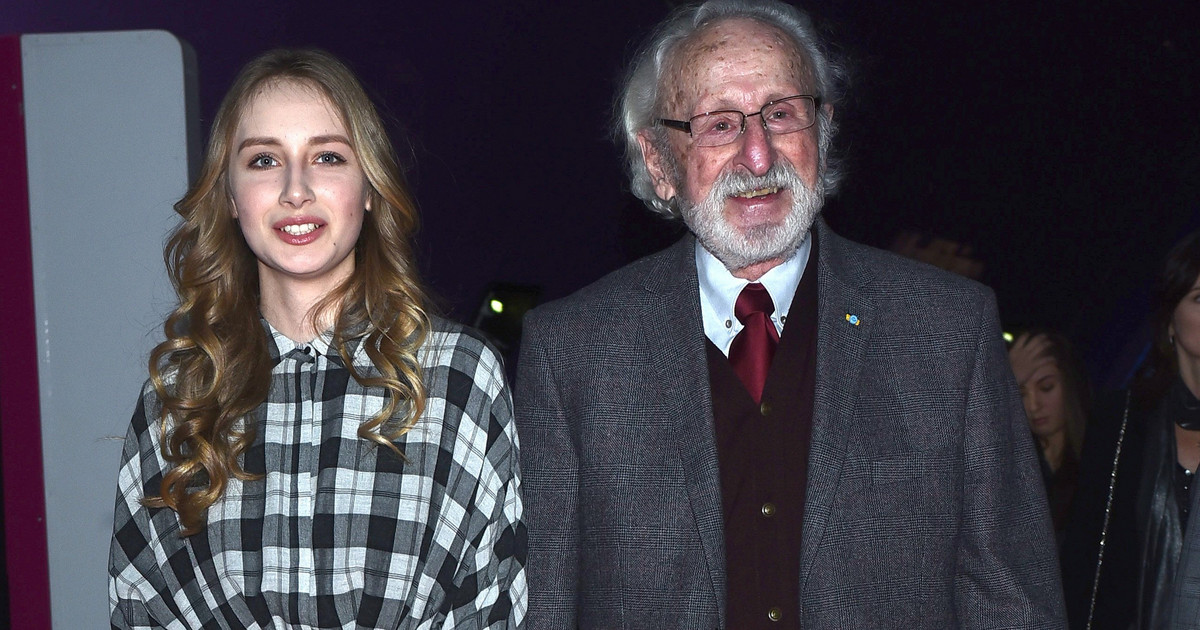

Christening is not without narration, editing, sins, messy cliches, and shortcuts, but it comes across as a film that is honest in its intentions. The director and his team sometimes manage to adapt styles directly from famous Italian cinema, the so-called Comedy all ‘italiana’. A comedy that talks about the most dramatic and experiments with irony and humor. A comedy that stores laughter and tears in one frame. A lot of this is due not only to the script, but also to the actors playing the lead roles (and we’ve got all the stars doing real acting here). Katarzyna Figura has something of the spunky Sophia Loren, the most famous mama in cinema history (“Mother and Daughter,” “The Italian Marriage”). Mariana has a distinct crack in her – on the one hand, she is the greatest Samaritan, on the other hand, she is a manipulator and an egoist. He is similar to the insane Tula, brilliantly played by Maciej Musiavski, whose charisma, sense of humor, or even a bit of grateful naivety can in no way be denied. Chrzcin’s heroes win the most when they let a certain — even brutal — situation get the humanity out of them.

“Amateur social media maven. Pop cultureaholic. Troublemaker. Internet evangelist. Typical bacon ninja. Communicator. Zombie aficionado.”