The method was actually tested at the polite request of Szumowska in “Daughter of God” (2019) – a film that was a step back in her career, a boring story with a dissertation preached without conviction. After this unsuccessful experience, Szumowska came to the conclusion that she was only able to implement her original projects that she knew perfectly well. And praise her for that, who if not her? Nobody pierces the soft tissues with such a lens, or questions their own image in the mirror, or makes them pierce their stomach. And if someone does not like it, it is difficult. “I can only be myself” – she convinces the director and allows her to persevere in this as long as her hero is Pam Bales (Naomi Watts).

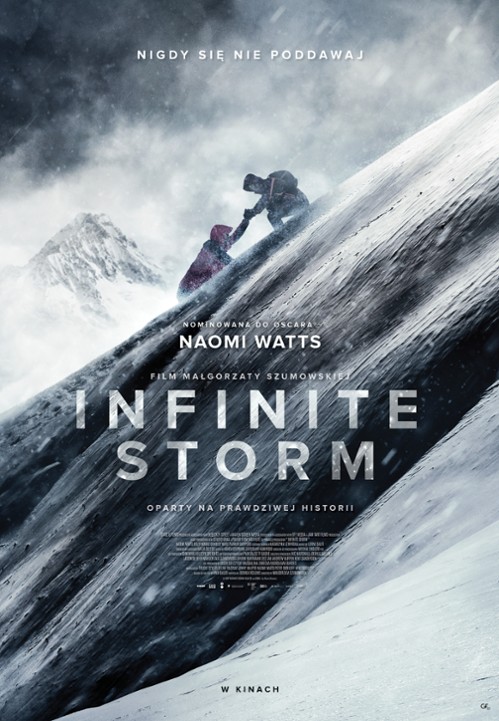

Infinite Storm seems to be a survival movie. However, since it tells a true story, the outcome of which can be learned by reading Ty Gagne’s press report “High Places: Footprints in Snow Lead to an Emotional Rescue”, it focuses more on the experience of extreme exertion than on the dramatic one. The solution. The silent study of the character and the novel Wading in the Snow is actually a silent dialogue between cinematographer Mickey Englert and actress Naomi Watts. Due to the fact that most of the film is devoid of dialogue, it is in these parts of “Infinite Storm” that it is easier to attract the viewer’s attention. The end of the protagonist’s attempt can be heard creaking shoes on the road, wind gusts, heavy breathing and heartbeat. The conviction that you are ultimately only left alone, confined to the confines of your own body, is quite a sad remark. The heroine does not trust anyone or anything. The world has let her down, and she has only the here and now who relies on her body and yet makes a life-threatening decision. This is not explicitly mentioned in the film, but the main point of the report is: “Ironically, one person’s dangerous behavior increased the safety of the other.” Because the savior might turn out to be saved. “The cloud cover turned from a canopy into quicksand, and the only thing stopping Balis in Gulfside were the sneaker marks in the snow,” Jani writes. Otherwise, the woman would have gone further, and most likely would have died herself. And so I became someone’s angel, and, by the way, I became their own.

As in many mountain films – from Zanussi’s “Spiral” to Jean-Jacques Anno’s “Seven Years in Tibet” to the documents of Eliza Kobarska – the struggle with the self becomes paramount. In the background the question resonates: are people walking in the mountains afraid of death, do they consider it, or rather bracket it or even defy it? It is said about climbers and climbers that they subconsciously want to die – they play with their fate and live in harsh conditions. But what happens when they are called normal people? After all, the unknown man (Billy Howell), who goes to the top of a snowy mountain in new shirts and weights, is like a sea-tourist from Papia Jura, who climbed the summit during the epidemic in January wearing only underwear, and whose limbs were also amputated as a result of frostbite. But it’s not a matter of no-braining, though “Infinite Storm” plays this state of disbelief well: How could someone possibly do something so stupid? (Szumowska also quotes the opening gag of “Body/Ciała,” when a corpse found on the Vistula River suddenly stands up and runs behind the police’s back, so as not to end up in the wake center.) It’s about self-destruction, and resistance to trauma: “If I’m going to survive, I must overcome it.”

The woman wakes up in bed – you can immediately see that she has not slept peacefully, her bony limbs scattered on the white sheets, as if after a long time someone found her body under the snow. She gets tired. Her body hurts, or perhaps it expresses pain that does not come from the body at all, we do not know yet. We get a report on the painstaking and realistic preparations to leave the house and go to the mountains. The starting point is the old comfortable everyday life from which the quit woman wants to break free – as if she wants to tire herself out to a point she doesn’t even think about. As if she wanted to go to the moon to beat the blues – mentally closer to her than Neil Armstrong played by Ryan Gosling from First Man (2018). However, it is not very dreamy, but only fierce.

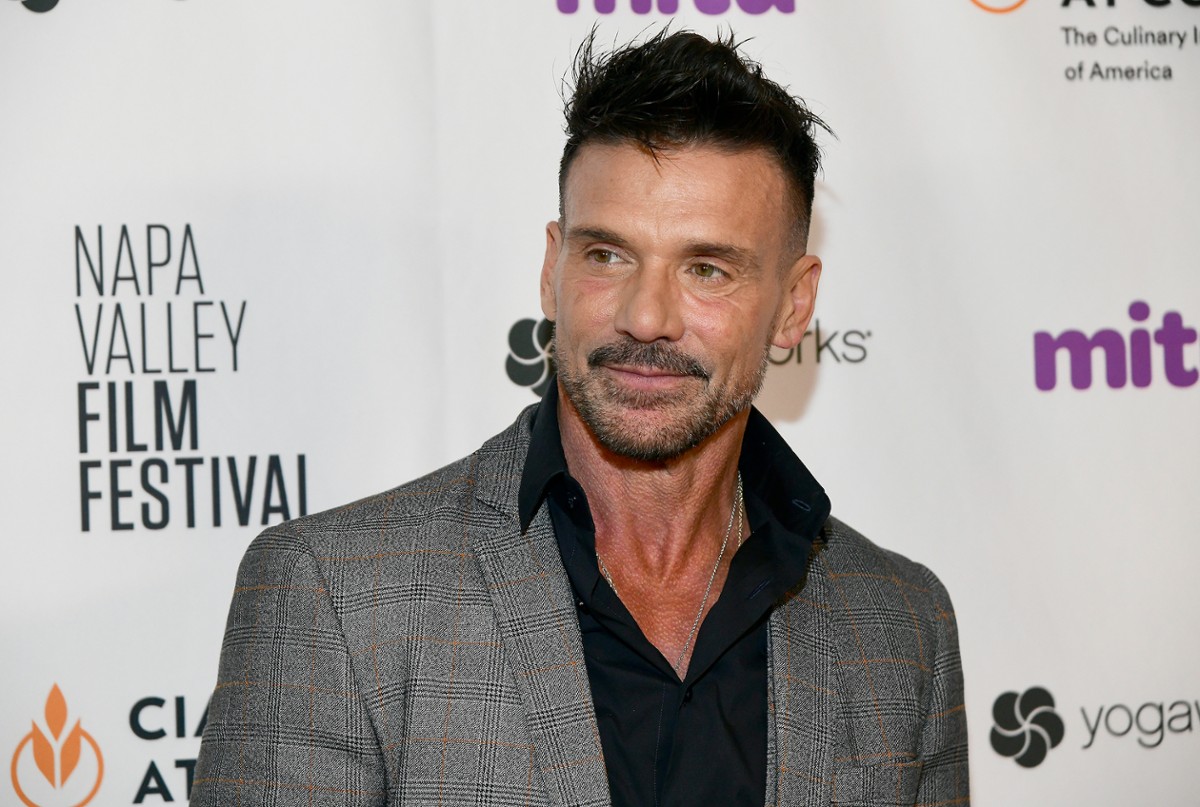

In late fall, Pam decided to spend the day trekking. Every hour here lasts forever, which every now and then the watch remembers and then flashes on the screen. Fully prepared, seems to be the safety chief – she left a map of the road she intends to cover behind the windshield wiper, and informs the others where she is heading. It takes into account that it might be “we can’t know” and “any day might be another day”. Fortunately, Szumowska leaves these cliches brief and tells the protagonist to remain silent – apart from the spectacle of singing country songs, which warms her image. Before the attack on the summit, there was also the phrase “you know what day it is”, which Pam says to a friend. She also sees an unfamiliar car in the parking lot, indicating that she will not be alone on the road. So, as viewers, we’re ready for the next rescue. It took centuries for Pam to find John unconscious (as she calls him, to facilitate communication). It’s a pity that the movie, unlike the book, didn’t explain that before you found it, she might have died herself. Howle plays an absent body, closed in on itself, who does not know what has happened. These two bodies – Rescued and Rescued (or vice versa, the report shows) – face death, testing their endurance. They dance the emotional tango. It’s amazing how strong Watts is and how accurate he plays when he’s totally exhausted.

With two actors set in raw Slovenia, playing the block of Mount Washington in the White Appalachian Mountains, Szumowska makes physical cinema focused on impressions, not words. Her heroine repeats over and over again: “John, are you okay?” Like the chorus to keep them alive. The effect is simple, devoid of manipulation, and therefore – forced delight. until that time. As long as there is silence, that’s great. The sound of breathing, the heartbeat, the creaking of snow under your boots – in short, the effort in difficult conditions is more than enough for a soundtrack.

Unfortunately, there is a temptation to directly name the symbolic role of women. “Angel” Echo – A song that tells us to see the intersection of the paths of a nurse and suicide through an accidental twist of fate. First, the pity of sprinkling begins to spray, then the Finger of God rises from the clouds, and finally it begins to flow – from the compressed throat pours an unstoppable stream of suffering. And when he let go of the dam that restrains pent-up feelings, the signs are no longer visible, everything sinks under a wave of focus. It falls to the bottom in the memories of the heroes, insistently explaining the “what” and “why”. “The mountains are my therapy,” says Pam, and the entire Infinite Storm should be viewed as a record of a therapy session. It is healing for the patient, and at times unbearable for the viewer.

So there are two films here. A radical message straight from the same combative body, dressed in gorgeous, blurred images of Michao Englert. We’ll find this movie in the middle of a snowstorm, at the bottom of an easy-to-fall crevice, in the eye of a hurricane. The operator constantly combines wide plans, when it is possible to cover the entire situation and details, when only hair or a black foot with frostbite is visible. To feel that we are in the middle of this situation, that we are being photographed by an “experienced” person.

The first part lasts about three-quarters of the show. It keeps you in check, ignoring the habits of the viewer – the caption music or the goal of the hero. Szumowska has the courage to isolate us from the music and lock us for long minutes in a suffocating trap, dressed as a mountain hiker, heading forward in a blizzard, that is, towards life.

There is also a second movie in which the heroes ran away. This movie and the movie, fortunately shorter than that and crammed into the end, is a lather-flavored weeping spectacle with memories of the happy moments seen facing the sun, as in an advertisement. The first film tames the element of cinema, has power here and now. The second is paper, it expresses the impotence of the past and the numbness of the director’s interpretations. As if Shumowska doubted that anyone in the United States would understand what she wanted to say, as if she was afraid of a lazy, ignorant viewer. So I will be angry – more faith in people.

“Infinite Storm” is another stone for the garden of Szumowska lovers. Again, the focus is on physicality, after all, body/body has been the director’s favorite topic since the beginning of her career, when she asked what would happen to him after death and who had the right to? (“What We’re Afraid of” 2006). Because every body has an end, and you have to remember it to appreciate it. So, in the school study Before I Disappeared (1996), I imagined waking up after the death of an unspecified person – perhaps the same? Bewitched reality in “The Soul Flew From the Body” (1997) and watched it burn in “Ascension” (1997), born to know why in “Silence” (1997) or become threatened with loss in “Happy Man” (2000)). It is precisely this type, focused on death, fearing the transcendent and being able to ridicule it, which the world saw when she received the Golden Tiger in Locarno for “33 Scenes from Life” (2008).

Somehow she manages to find poetry in everything, humorous, without fear of pity or brutality. As I became interested in the body, I tried this suit of many characters, including the salable commodity body (“The Shepherd” 2011), the repressed, celibate (“In the Name of…” 2013), the disfigured and suffering (“Body/Body” 2015), Captured and taken back (“Twarz” 2017) or lonely, hungry for tenderness (“Never Snow Never Again” 2020). I began to explore the point where the astral body meets the physical body. It searches for an aura that is rarely visible (“Ono” 2004). It creates extreme situations in which we strip off one body to reveal the other. One of these situations we encounter in The Infinite Storm.

The theme of the mountain expedition on the verge of life and death appears to have been created for Szumowska and her regular collaborator, and most recently, official co-director, Mikai Englert. It is said that their cinema is made largely of editing. But this time they failed at this point. Similar to the text itself, it insistently explains the heroine’s motives throughout the final code. The film’s weakness is the apparent dichotomy between present, reflexive and reflexive. Like Pam Bales, Szumowska is best when you go to the item. This time it didn’t make it to the top, but sometimes that wasn’t what a successful trip was all about.

“Amateur social media maven. Pop cultureaholic. Troublemaker. Internet evangelist. Typical bacon ninja. Communicator. Zombie aficionado.”

![Back to Those Days (2021) – Movie Review [Kino Świat] Back to Those Days (2021) – Movie Review [Kino Świat]](https://www.moviesonline.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/1638111081_Back-to-Those-Days-2021-Movie-Review-Kino-Swiat.jpg)