But are they really primitive beings? Recent experiments show that yellow, single-celled things that don’t even have brain buds are surprisingly smart, they even have such a thing as memory!

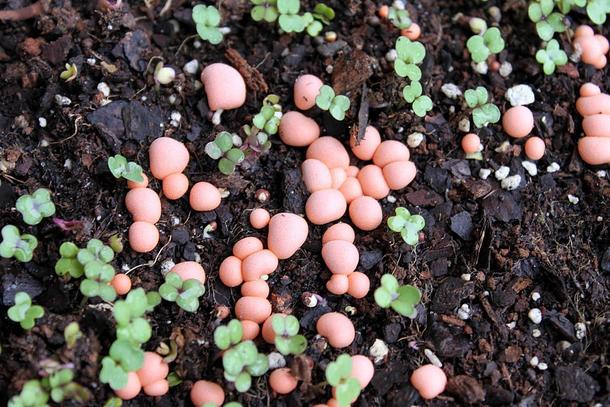

Slime looking for food

Scientists often experiment with types of slime mold Physarum polycephalum, also called Blob, because it is one of the few species that can reproduce in the laboratory. – They can survive in hibernation for a very long time, – says Stanisław Łoboziak. – In my laboratory, I have such slime molds in a dry state, when they do not develop, but after adding water they will quickly create a slime, i.e. a multinucleated cell, which with the help of pseudopods begins to move in different directions in search of food, – explains the biologist.

And this heading in different directions is by no means accidental, as scientists from Harvard University have proven. They began experimenting with sticky mold, which they placed in the center of a petri dish, which is a round glass dish with low side walls. On these walls, they placed four glass discs simulating food, three discs close together on one side of the tube, and one slide on the other. as it turned out? When the slime mold began to release its lying legs, it directed them all towards the edge of the dish, on which there were three disks, and did not care at all about the opposite side, where there was only one. In short, a single-celled, brainless organism with no sense of smell or sight somehow knows where there is more food and is headed that way. How did he know where were three balls and where was one? Scientists have no idea.

Slime mold road in the maze

Likewise, it is not known how slime blocks can find their way through a maze. Such an experiment was conducted by a team of scientists from the Japanese Biomimetic Research Center in Nagoya. They put a sticky block in the middle of a classic maze, and put a little food in its two exits. The slime mold quickly overwhelmed all the paths of the maze, reaching for food, what’s more, its parts at both exits were connected by additional threads of the slime mold. To the amazement of the researchers, it turned out that they had followed the shortest possible path that could be bypassed in the labyrinth. How did slime mold draw this path? How did he come up with such complex thinking? This is also a great puzzle.

Moreover, slime molds can pass on knowledge to each other – for example, about toxic substances. This has been demonstrated by scientists from the University of Toulouse, who have built a special practice field for slime molds. It consisted of two flat spaces separated by a bridge. On the bridge, the scientists poured salt (not grainy but harmless to slime molds) and placed food behind the bridge. Then they trained 2,000 clay bricks to cross the bridge and ignore the salt. Another group of 2,000 clay bricks learned to cross a clean bridge. The researchers then grouped the slime molds into pairs — those they knew salted brisket was harmless, and those they hadn’t been in contact with salt. However, some pairs were made of two sticky clay molds slathered with salt. It turned out that those pairs in which there was a clay mold that knew the salt and the one that was not in contact with it passed the bridge without any problems the first time. And the slime blocks that first came into contact with the salt escaped from the sternum. It seems that in mixed pairs, the slime mold who knows the salt remembers the material and somehow tells the latter that there is nothing to be afraid of …

Slime molds and railroad tracks

Japanese mycologist Toshiyuki Nakagaki also conducted another experiment that amazed the scientific world. In it, he spread portions of oatmeal on the table, redrawing a map of Tokyo and other Japanese cities. Then he put a sticky mold in the middle, which began to move towards the chips, perfectly reproducing the intercity rail network in Japan.

“Slime molds undoubtedly possess not only a kind of alien intelligence, but also memory. For example, it has been shown that they are able to remember the regularity of flashes of light or the places where they have found food before,” says Stanisław Schubuziak. The scientists also conducted an experiment in which they In it he blows cold air on the sticky mold at the appointed time during the day, and perhaps it was not very pleasant for him, because after that it stopped spreading, as if he was trying to wait out bad conditions.After several days of blowing at the same time, the scientists saw that the next day It seemed that slime mold was waiting to explode at that time—it had stopped moving a moment earlier. He knew full well that unpleasant air was about to be blown in. How did he know? How did he remember it and how did he read the time during the day? These mysteries are still waiting to be solved.

Echo Richards embodies a personality that is a delightful contradiction: a humble musicaholic who never brags about her expansive knowledge of both classic and contemporary tunes. Infuriatingly modest, one would never know from a mere conversation how deeply entrenched she is in the world of music. This passion seamlessly translates into her problem-solving skills, with Echo often drawing inspiration from melodies and rhythms. A voracious reader, she dives deep into literature, using stories to influence her own hardcore writing. Her spirited advocacy for alcohol isn’t about mere indulgence, but about celebrating life’s poignant moments.