You May Also Like

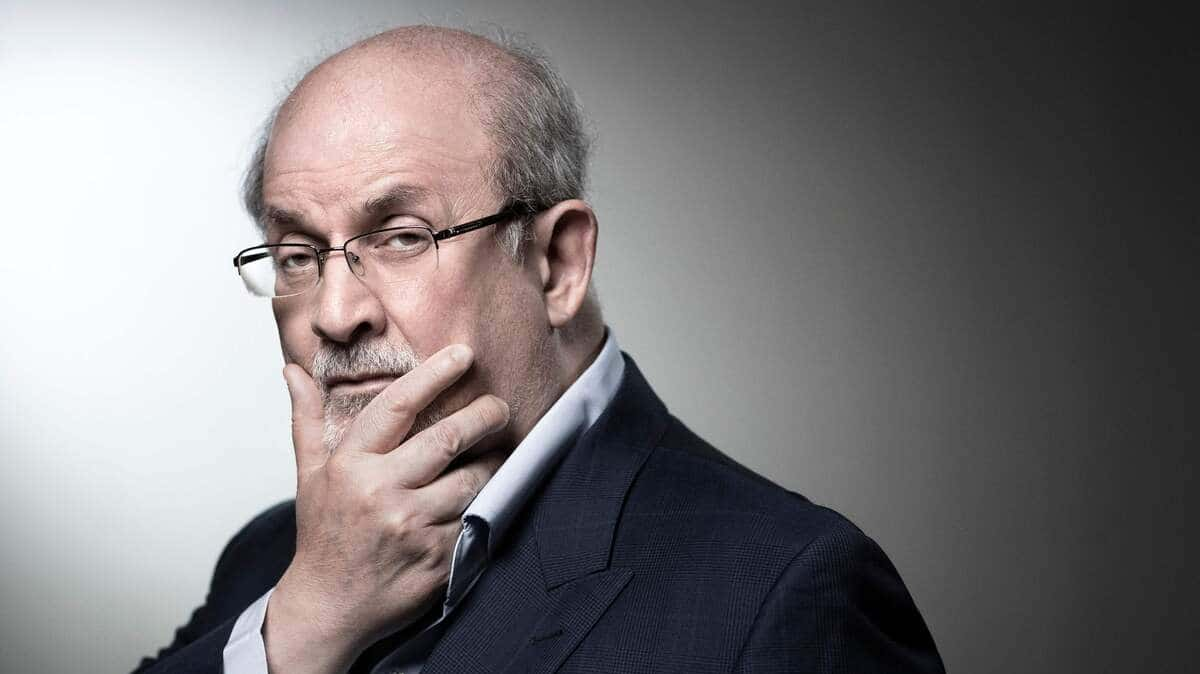

Salman Rushdie lost an eye and an arm

British writer Salman Rushdie, who was stabbed in the United States in…

- Stephan Terry

- October 23, 2022

Will Patrick Benoit look to replace Gino Chouinard at the helm of Salute Bonjour?

The mourning stages for the team have already begun hello hello Who…

- Stephan Terry

- December 26, 2022

5 Hair Trends to Watch for Fall 2023

The colors, cuts and accessories of the season will create stellar hair…

- Stephan Terry

- September 10, 2023

Elias sees Peter Fazardo entering his house: “It’s not customary to follow me” | Eye view

Updated on 11/22/2021 at 08:52 am Elijah Montalvo He passed his first…

- Stephan Terry

- November 22, 2021